Tragedy on the Thames

The Princess Alice pulled out of Gravesend and headed back up the Thames at just after 6.00 pm. The passengers, who had paid 2 shillings for the day trip must have felt that their money was well spent. The weather had been kind although by 7.40 pm, as the boat approached Woolwich, pier to disembark some of the sight-seers, a chill had descended which led the Rev. Gill to go from the front seat of the saloon deck, inside to the saloon cabin where there were about fifteen people. Suddenly there was a crash and William Alexander Law, second steward on board the Princess Alice, said to the stewardess “There’s some barge alongside.” Another crash and Law ran up to the deck where he saw unbelievable carnage.

… amid the confusion and screams of the passengers I heard the water rushing in below, and saw that we were sinking. I then rushed to the top of the saloon gangway and shouted, “Come on deck; we are sinking.”

Tuesday, the third of September 1878, was a fine day for an excursion. Around seven-hundred men, women and children took advantage of the weather to cram aboard the saloon steamer, the Princess Alice, for a day on the river. The boat left London about 11.00 in the morning, heading downstream for Gravesend, a distance of thirty-one miles, and from there, on to Sheerness. The trip to Gravesend normally took less than ninety minutes and once there, many of the excursionists went on to one or the of the tourist attractions, for Gravesend was becoming a popular resort town in the nineteenth century.

By Tuesday evening the weather had turned “muggy” and tired but happy the excursionists boarded the steamer at Gravesend for the “moonlight” return to London. The Rev. Mr Gill, who had gone to Sheerness for the day, noted that “the passengers on board were a quiet, well-behaved, and respectable company.”

Meanwhile, in the saloon cabin, the Rev. Mr Gill heard a grazing and grinding of the side of the vessel, then a sudden stop, and then a terrible crash of shivered and splintering timbers.” Running from the cabin to the lower deck on the port side, he saw the bows of the huge iron-cased ship towering above as high and inaccessible as the walls of a castle.

It was the Bywell Castle, a newly repainted steam collier of 890 tons bound for Newcastle to pick up a cargo of coal for Alexandria, Egypt.

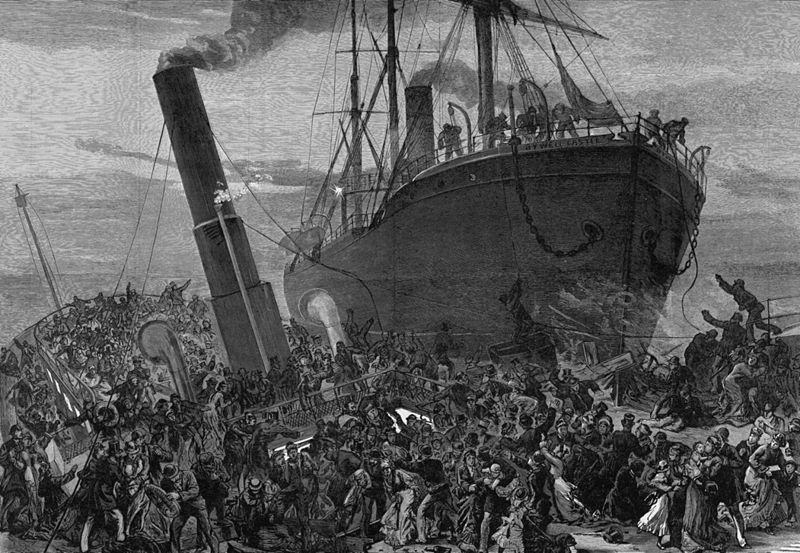

In the ensuing chaos, those passengers who could, rushed to the rear of the steamer. Some threw themselves into the water, others attempted to climb aboard the Bywell Castle, and a great number were trapped below decks when the two boats collided. The Rev. Gill saw that a few were hanging onto the chain at the bows, but what was one chain for 700 people, most of them helpless women and children, all crowding and trampling one another in a boat which was doomed to sink in a minute or two? The shrieks, ejaculations, prayers, and wails of helpless agony were heartrending.

Lucy Sophie Bridgman (nee Collard)

Although there were a dozen or more lifebuoys on board and several lifeboats, the accident took place with such speed it would have been impossible to organize their use. Although every effort was made to rescue the survivors, there were very few and many died in the weeks following as a result of the terrible and toxic industrial pollution of the Thames. Of the approximately 700 on board the Princess Alice, the best estimates suggest that 600 died either in the crash or as a result of the collision.

William Bridgman and his wife of two years, Lucy were on board the Princess Alice and drowned that day. Their five month old son Frederick Collard was left an orphan. Three years later in 1881, Frederick was lodged in the Infant Orphan Asylum in Wanstead, Essex. He remained there to at least 1891 (aged 13) and was schooled in the Asylum.